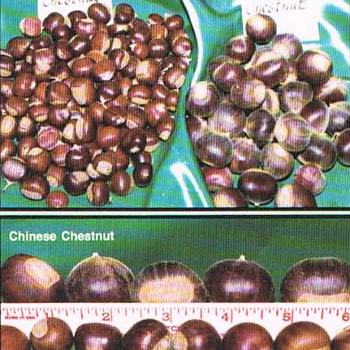

Sweet-Hart Chestnut

Castanea dentata x mollissima 'Sweet-Hart'

Around 1906, the chestnut blight, Endothia parasitica, was introduced along the east coast of the United States and spread like wildfire through the forests. Devastating the once dominant American Chestnut, Castanea dentata, the blight had little to no effect on the Chinese Chestnut, Castanea mollissima, that were prominent throughout Asia. (Learn more from The American Chestnut Foundation ®)

In 1944, Mr. & Mrs. Bert Harter of Doylestown, Ohio were given three West Virginia Sweet Chestnut trees by Dr. Cather in order to help build their family orchard. The Harter's purchased subsequent Chinese Chestnuts of the "Hawk Variety" in 1946 from Mrs. Estella Hawk. After some years a hybrid was found growing among the orchard trees. Aborist, Dr. Oliver Diller, was in charge of finding a substitute for the American Sweet Chestnut at the time and was working at the Ohio Experiment Station in Wooster, Ohio. In 1961 he declared the Harter Chestnut the best sweet flavored chestnut found by his department and the USDA in Ohio. Practically a perfect cross between the two chestnuts, the Sweet-Hart was not only blight resistant but also a wonderful producer of sweet chestnuts. Boyd Nursery Company named the new chestnut the Hart Chestnut in honor of Mr. & Mrs. Bert Harter after Mrs. Mary Harter agreed to the new name. Producing pale yellow flowers throughout June and chestnuts throughout the summer, animals absolutely love the chestnuts and the tree makes an excellent addition for deer, turkey, and other wildlife plots, as it is a more consistent producer of food than oak trees.

Drake, Robert J. "Chestnut Crop Yields Profit, Finances Hobby." The Plain Dealer [Cleveland, OH] 30 Oct. 1961: 51. Print.

Encyclopedic Entry

According to Michael A. Dirr's Manual of Woody Landscape Plants ...

Consuming Chestnuts

Harvesting Chestnuts - First and foremost, never remove burrs from a chestnut tree. Removing burrs increases the risk of injury to the chestnut tree, and burrs still on the tree are typically not mature. They may contain nuts that are green or not fully formed. Similarly, green burrs that have fallen to the ground should be left in place. These burrs are not yet ready to open, and will open themselves in a few days. Only then should the chestnuts be collected. Green chestnuts have no market value, as their taste is too bitter for consumption. Second, there is a method to opening ripened burrs for chestnut collection. Never open burrs by stomping with your feet. This will only crush the chestnuts inside of the burrs. Instead, it recommended you roll the burr under your foot, applying even and constant pressure until the burr either breaks apart or the nuts fall out onto the ground. If at any point you feel you may crush the burr using this method, move onto another burr. The burr will likely open when tried again in the next few days.

Washing Chestnuts - Because of their high moisture state (nearly 50%) and the nature of dropping and ripening upon the wet ground, chestnuts are highly susceptible to mold growth. Chestnuts may have mold and fungal spores upon harvest, and should never be washed together in a bath. A water bath only serves to transfer mold and fungal spores between the chestnuts. Instead, chestnuts should be washed individually under a warm water stream. A hot water bath should be only be considered as a last resort (mold already showing on chestnuts). In this case, the water must be at least 140° F and the bath should last at least two minutes. Be careful not to heat the water much warmer than 140° F or you will risk partially cooking the chestnuts. It is important that you avoid eating any chestnuts where the black mold may have entered into the chestnut kernel. For these chestnuts, a last resort bath is not enough. Chestnuts should only be washed with treated water or fresh domestic well water.

If you suspect that chestnut weevils may have infested some of your chestnuts, the hot bath is your only option. For chestnut weevils, the bath must be at least 120° F, and the nuts must be soaked for at least 20 minutes. Like with the mold treatment outlined above, the water temperature is very important. Too cool and the weevils will remain alive. Too hot and the chestnuts will partially cook. When you have finished washing the nuts, air dry the batch before storage.

Storing Chestnuts - As long as you plan to consume chestnuts within two to three weeks of harvest, refrigeration is sufficient for storage. In the fridge, chestnuts can either be stored in a container or on a tray. If your plan is more long term consumption, dehydrating the nuts is the way to go. Dehydrating the chestnuts will reduce the water content from 50% to approximately 7-8%. We recommend a dehydrator set to 100° F for 12 hours. For more information and a nifty series of step by step videos, visit the Wiki How page on Drying Chestnuts. Once dehydrated, chestnuts will store for several months in a sealed dry storage container. Once dried, they can also be stored in the freezer; however, once frozen, the texture of the nut will forever change. Frozen water crystals inevitably expand and break up some of the nut’s tissue. For many chestnut connoisseurs, this is unacceptable.

Preparing Chestnuts - There are many delicious recipes that feature American hybrid chestnuts, but the most heralded is the holiday classic – roasted chestnuts. Homemade roasted chestnuts smell wonderful, and today, they are all too often forgotten tradition in spite of their Christmas Song heritage. Below is recipe for perfect roasted chestnuts.

You will need the following: A serrated bread knife, a cutting board, a slotted spoon, a saucepan, a mesh strainer, and a baking sheet.

- Preheat your oven to 425° F.

- If your chestnuts are dried, rehydrate your chestnuts by soaking them in water for one hour prior to preparation.

- Prepare you chestnuts by holding them tightly between your thumb and index finger. Carefully slice across the rounded crest of the chestnut with the serrated bread knife. Use caution as the shell is slippery. You should aim to slice the chestnut in a single motion; however, gentle back and forth sawing motions are ok if you cannot achieve a single cut. Take care to cut all the way through the shell. Two perpendicular slices are recommended. A chestnut slicing tool can be particularly helpful.

- Place the chestnuts into the small saucepan and cover with water. Bring to a simmer.

- Once the water reaches a simmer, remove the chestnuts from the water using the mesh strainer and the slotted spoon. After water is allowed to drain, transfer them to a baking sheet.

- Roast the chestnuts for 15 minutes or until the shells begin to peel where your shell cuts were placed.

- Remove the chestnuts from the oven. Place them into a bowl and cover with a towel for 15 minutes. This will allow the chestnuts to steam and ultimately make them easier to peel.

- After the chestnuts have rested, simply pull the shell aside. The chestnut should slip out. Both the outer shell and the brown skin surrounding the chestnuts should be peeled away. If any nuts appear to have lost their integrity and become mushy, throw them away as they have spoiled. Furthermore, if the nuts have black spots, throw them away. These nuts have fallen victim to chestnut weevils. Nuts that appear dark brown after peeling have been ruined due to mold and should also not be consumed.

- Serve and enjoy!

Considerations when Planning a Food Plot

Types of Food Plot – There are two primary types of food plot – cool-season plots and warm-season plots. Quarry during both periods typically include bear, deer, rabbit, raccoon, squirrel, and turkey among others. Warm-season plots (as the name implies) are for summer hunting. The focus of warm-season plots is typically food high in protein and tonnage since wildlife forage options can be inconsistent during summer droughts and protein is necessary to rebuild winter season muscle loss. Cool-season plots have a different focus. As winter approaches, wildlife diets change to foods that typically higher in carbohydrates and fats. This energy helps sustain wildlife activity during the winter. It is in this regard that chestnut trees excel.

Location – The overall effectiveness of a food plot depends on its location. Optimal locations are easiest to identify with the aide of topographic maps and aerial photography. You can get a topographic/aerial map of your property at the United States Geological Survey agency website. From the topographic/aerial map, you can determine relative slopes, clearings, and flood plains. From this information one can surmise where the best soil (valleys and flood plains), sunlight (clearings), and access (roads or trails) are on your land. You can even go a step further and test the soil of your prospective locations with a soil kit (purchasable online) or by taking a physical sample to your local county agricultural extension agency.

Mast – Mast is food. More specifically, mast is the fruit (mostly nuts) accumulated on the forest floor which serves as nutrition for animals. You can find all sorts of information regarding the best nutritional food plot candidates for the greatest agricultural efficiency. Just like in landscaping, the aim of an excellent food plot is to provide a steady focus over time by minimally overlapping the fruit/food source appearance. Not surprisingly, certain plants are better for different quarry, and a well thought out plot can bring quarry back over several generations. Many times, the best resources are written by state university agencies - University of Tennessee, Mississippi State University, University of Alabama/Auburn University. When it comes to deer and turkey, chestnuts (especially sweeter varieties) are extremely popular through the October and November months. Unlike acorns (another popular mast), chestnuts contain almost no bitter tannin making the nuts very sweet. Chestnuts are also generally faster at producing nuts – bearing fruit in five to seven years. In contrast, most oak species take close to 10 years or more to bear acorns (Sawtooth Oaks are an exception). Furthermore, chestnut trees bear nuts every year where oaks only bear acorns once every two years.

Where can the Sweet-Hart Chestnut be purchased?

We currently maintain a private orchard of Sweet-Hart Chestnut trees on our farm. We are in the process of producing viable stock for the coming year (2021). If you are interested in reserving Sweet-Hart Chestnut seedlings upon availability, please visit our product listing page.